Grading, and Other Existential Questions by Dana Paz

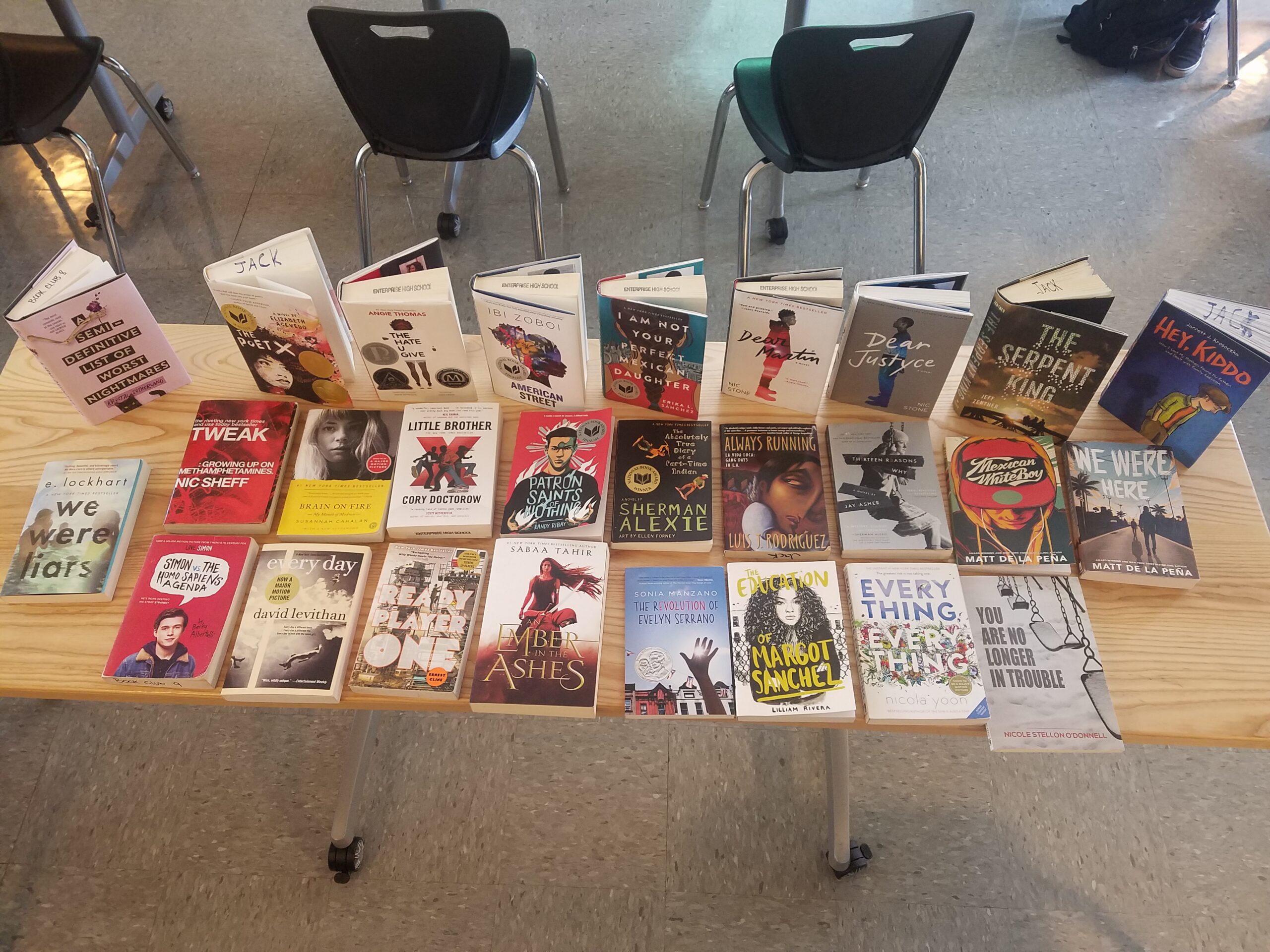

Since I started teaching, few things have occupied my thoughts like grading. I’ve tried many grading approaches (grading scales from 1-100, holistic grading, standards-based rubrics, even (gah) students grading themselves). All I wanted was to find the fairest way of grading—an approach that honors what students can do, that shows them clearly where they are in terms of meeting what is expected of them, and that focuses more on learning than behavior. This is a lot to ask of a grading system, but I was determined to try. So I decided to embark on an inquiry project to implement a 4-point, standards-based grading system. I found that even thinking about grading in these terms made an impact on my approach to teaching, and interacting with students. Further, I found that students, parents and other teachers were thoroughly confused by this new system, even while they liked the effects it had on their grades. My findings played almost like a stream of consciousness in my head—made up of different voices (my students, their parents, my colleagues, and myself), so writing “bricks” or vignettes of these thoughts made perfect sense as a way to present my findings. Then, when I was reading my words back to myself, I started seeing a movie in my head that I wanted to share. Hence, the videos, which you can watch by clicking on the title of each vignette.

Problem of practice: how can I stop grading on behavior, as this invariably affects the same kids, every time.

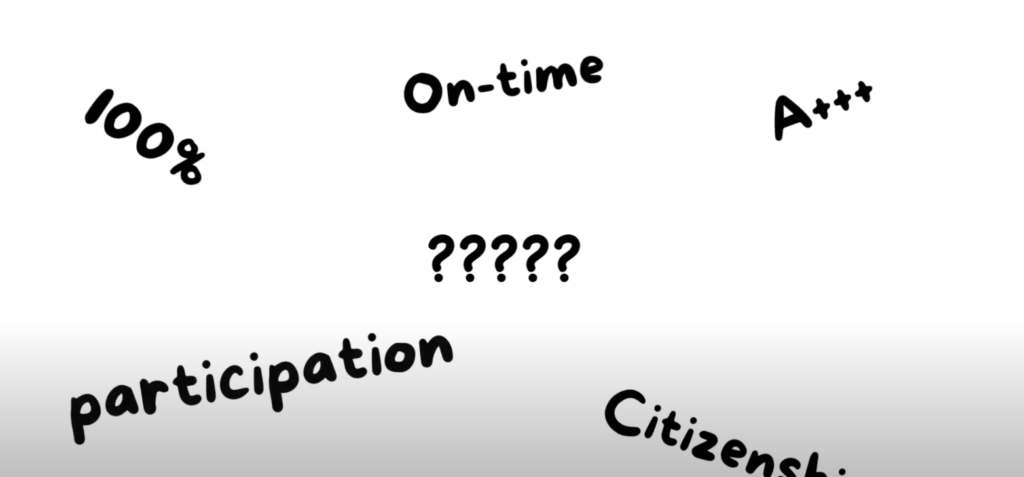

What do you mean, “Grades are arbitrary?”

You’ll be assessed on reading, writing, speaking and listening. That’s what we do in English class. Mr. Ellington gives an automatic ZERO if you don’t capitalize the i. Because as an 8th grader if you can’t do this you obviously can’t do English. She is so with it during our class discussions, and she really gets the reading, but her grades… What does she need help with? Well, she didn’t do the big essay so she can’t get better than a D anymore. His work is genius but it’s always late, so that’s why he’s failing, Mrs. Robinson. Because he is being assessed on reading, writing, speaking, listening and punctuality. In THE REAL WORLD, you can’t get away with just phoning it in. You need to make an effort at everything you do or you won’t get paid. Is this true? Does everybody know this? Because I don’t think your REAL WORLD and my REAL WORLD are the same place. A 50% means you fail at reading because you can’t tell me half of the events that happened in Ch. 4. Wait, if I can’t tell you half of the events, doesn’t that mean I can tell you half of the events? Yes, but this is English, not Math, so pipe down.

Explain – Tweak – Repeat

Step one: apply a grading scale of 1-4. This is fairer than the 100% grading scale because there is only a one-point difference between an F and a D, rather than a 59 point difference. A (4) is an A. It means you really get it; you get it so well that you could teach it. A (3) is a B, it means you mostly get it, but it’s not perfect. Huge parenthesis (I am aware here of a deep truth within myself and that is that I am a walking 3: I mostly get it, but it’s not perfect. I feel this is true for most people.) A (2) is a C. This is not average, because by now I have learned that “average is a myth”. It means you don’t get it YET, but you will get it if you add the highlighted items in the rubric. A (1) is a D, and if you get a (1), it is code for “you didn’t try,” or, “you left most things blank.” After much explanation and tweaking, most people get the 4-point grading scale. There are fewer As. There are also far fewer Fs, and a seemingly balanced amount of Bs, Cs, and Ds. In fact, more and more teachers are using it. So, I am now ready to keep explaining and tweaking.

Step Two Hundred

One of my colleagues said, “I started doing learning targets in my gradebook and I’m never going back! Now I can tell students exactly what standard they need to work on when they’re concerned about their grades!” The exclamation points actually hung around her head as she said this. I thought Ok!!!! I will try this. Though many question marks hung around my head. For instance, how many students will give a hoot about learning standards anyway? And, could it help me plan? And know what to reteach? And give me more valuable information to share with parents? And have an answer for the constant, Why are we learning this? Then came the week-long project of translating a zillion standards into student-friendly language, with big, healthy air-quotes hanging in the air around those words. My idea of “student-friendly” is not everyone’s idea… So many iterations later, I had my list and was ready for the gradebook. I am the kind of person who just naturally has more question marks than exclamation points surrounding me.

Ands Buts and Sos

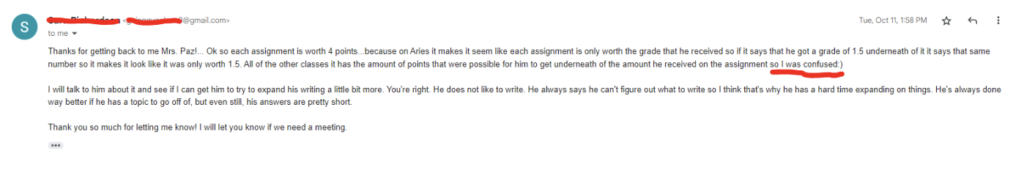

Aries assignments are (one) record of a teacher’s accomplishments. (Trying not to think of that sea of red). Last year, it read, “Narrative Essay.” This year? “I can engage the reader by providing descriptions of setting and characters,” and “I can use narrative techniques like dialogue and reflection to develop the story.” What assignment is that? Help me understand your gradebook. Was this a worksheet? Was this a quiz? Well, I’m doing it this way because it helps me break down what students can (will) or can’t (won’t) do. No, other people don’t understand it at first, including parents and students. (“Can you tell me why Josh has a C? He’s not missing any assignments.”) BUT, I can now show students and parents at a glance where the struggle is. (“Josh is very smart and a pleasure to have in class. However, his writing is very brief and he has missed including some of the elements we discussed in class. You can see with the breakdown in Aeries that his reading learning targets are at a 3-4, and his writing learning targets are at a 1-2.”) AND, as I pulled out last year’s assignments and went to “translate” to a standard, I found that some of them DID NOT MEET ANY STANDARD AT ALL and were just BUSY WORK. Does anyone really need to be more busy? AND this alone has been valuable, not because everything we do must meet a standard, but because if it doesn’t, I want to know that. AND this has been a way for students to understand their learning targets, or at least be consistently exposed to them. AND at a glance I can now look at my gradebook and see the balance of learning targets between speaking, listening, reading and writing. Holy cow, we sure do have a lot of reading, and not very much listening. SO I will stay the course AND tweak and explain (always tweak and explain), BUT I will stay the course.

Any Given Day

We are starting our narrative essay. Write about an experience you’ve had. Here is a model. You see how the writer introduces the characters? They establish the point of view, here. You see the setting? The exposition as a whole? That is important. Note the description! The figurative language. The imagery! That is important. Do you see how the author has captured character traits through dialogue? And reflection? That is important. As writers, the most important thing is to make the reader FEEL something. And remember, add a conclusion! Don’t leave us hanging! That is important.

Questions?

“How many sentences does this have to be?”

They just sit there.

“They just sit there.” This is true in my class. In other classes, these same students do more than just sit there: “Mason was drawing inappropriate male anatomy parts on another students arm during class.” “He told me ‘go to hell/fuck yourself’ in Spanish”. “Chris was kicked out of class for being disruptive (tripping kids while running, grabbing boys in their private parts, using profanity).” “Repeated disruption and disrespect. While trying to talk to the whole class she interrupts the whole time with her own little comments. One of the comments she said included the F word. I cannot teach with her in my classroom, the whole class misses out on half of instruction time because she takes over class.” So yes, in my class, “they just sit there.” Dare I call that a win? They are quiet. They are listening – I think? Every once in a while, they’ll comment on our class discussion. Yes, “they just sit there,” but they don’t leave. They are failing multiple classes, but in my class they get a 1, because “they just sit there.” No, they’re not meeting the standard, and they know that they are woefully shy of meeting the standard but they’ll also not be tossed overboard with an F around their neck . At least the kid who is in there scrawling IDK on pieces of paper is there, and maybe at some point he’ll talk. Maybe at some point he’ll get past the idk. But he definitely wouldn’t if he wasn’t sitting there.

Dana Paz received her BA in Social Anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley in 2005. She lived and worked in her native Guatemala as a grant writer for international development projects for 12 years. She relocated back to California with her family and received her Masters in Education at Chico State in 2019. She is in her fourth year of teaching English Language Arts to 7th and 8th graders at CK Price Intermediate School in Orland, CA. As an immigrant from Guatemala who found academic success relatively late in life, Dana strives to build her students’ confidence in finding their voice. For her, the best part is the immense variety of what students share and the moments of genius that come through. When she’s not teaching, writing or reading, Dana enjoys long bike rides, hiking, yoga and spending time with her husband and son.

In the Summer Institute and throughout the year, Northern California Writing Project teacher consultants are invited to engage with in-depth writing prompts in generative groups. We believe classrooms hold the world inside of them, and teachers witness the impact of family systems, larger culture, local communities, political debate, and public health, alongside their own lives. Dispatches is a place where we explore these intersections and tangles, joys and impossibilities, with the aim to honor our educators and those they teach.