Dispatches: You Are the Scale of the World: Fragments From a COVID-Era Classroom by Robbin Jack

Welcome to NCWP Dispatches.

How do we chronicle our days in a time that resists narrative? Like living through a long body of paragraphs, by the time we get to the conclusion, the introduction has changed. The memory of March is a distant cousin to the reality of August. And so we write missives: a memo, a letter to an old friend, a late night text, a doodle in the margins. Or perhaps a recipe, a rant, or an unsent email draft–forms that hold the capacity for uncertainty, story spaces already ceded to unknowing. In other words, the ephemera of this moment. With this in mind, this summer, the Northern California Writing Project hosted a space for a group of teacher consultants to write weekly, tracking their experience, observations, and process as they navigated the transition between the initial pandemic response in the spring to the impending, more-intentional classroom spaces created for fall. We called them Dispatches. Representing a range of grade levels, teaching contexts, and expertise, these educators created a writing community where deep dives into anti-racist pedagogy wove through questions and concerns about teaching communities, daily writing practice and illustrated mini essays resonated with one another, and over time the fullness of our experience came into focus.

Kitchen tables are now recording studios. Entire worlds are offered and built through the laptop’s persistent eye. Never before has the classroom felt at once so public, and so private, siloed in our homes or offices, away from students, colleagues, and campuses, trusting, hoping, our videos, documents, and discussions are finding their destination. As we stretch, week by week, into a school year like no other, we offer you the Dispatches from this summer’s writing, revised and expanded to include the ever-evolving challenges of teaching and learning, right now.

–Sarah Pape, NCWP teacher consultant and Dispatches coordinator

You Are the Scale of the World: Fragments From a COVID-Era Classroom* by Robbin Jack

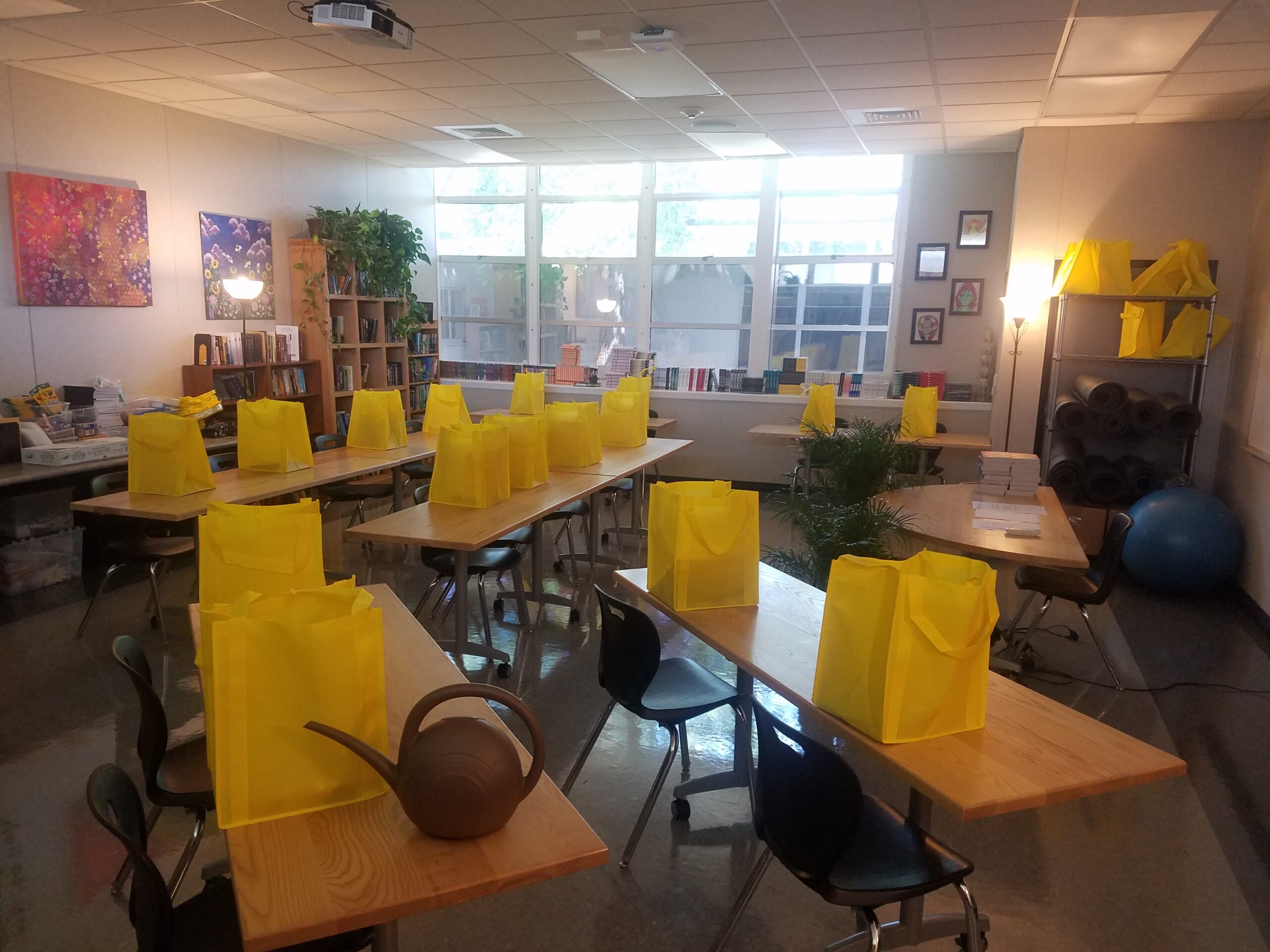

I. The teacher slips on her paper mask in the parking lot, fingers slipping over the light blue edges, looking for gaps that could kill. Inside, she begins the task she has dreaded for weeks, breaking the long wooden table apart, into individual segments, now distanced. They look lonely. She stacks boxes of markers and pencils and post-its into piles and begins to fill bright yellow bags with the tools needed to create vibrant maps and models of the earth’s crust, and stories of lives lived, histories of families, poems of young love, graphs of the length and width of the football field. She measures six feet between chairs, six feet between children breathing, six feet marked with blue tape on the floor, a moat no one may breach. She builds a cache of the weapons of this new war: bleach wipes, sanitizer so cheap it smells of bargain tequila, the one precious bottle of Lysol she found hidden one early morning on the market shelf behind the dish soap. Her year always starts in September and this one brings the same dream the past ones always have: that they live, that they all, live.

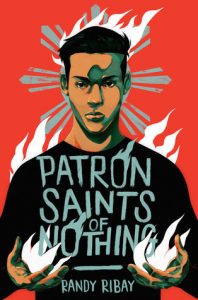

II. The brother and the sister board the plane, hovering too near each other, craving connection. The plane lifts and rises above the verdant, lush green of their native Philippines, each foot lifting them further away from anything that ever felt like home. They are teenagers in the bodies of small children. Time zones away a teacher sits before a stack of books trying to choose, sending up pleas to whatever gods that might be to guide her hand to the story that holds the potential for solace and connection and familiarity in this global time of crisis, fear, and loneliness. The brother and sister silently step into the classroom, hovering too near each other, craving connection, the only two bodies in the room allowed to remain closer than six feet, a small but potent gift. Four huge brown eyes lift and move slowly around the room. Two small bodies remaining perfectly still, skin prickling in the presence of so many other people, public school for the first time ever. The teacher explains how to combine simple sentences from eight feet away. The brother and sister hide their elegant grasp of English at all costs; they are not yet ready to offer this new world their souls in words. After grammar, the teacher places a copy of the novel in front of them, one each, the story of a Filipino American boy. The brother and sister open the red cover and begin to read their own story, in reverse.

II. The brother and the sister board the plane, hovering too near each other, craving connection. The plane lifts and rises above the verdant, lush green of their native Philippines, each foot lifting them further away from anything that ever felt like home. They are teenagers in the bodies of small children. Time zones away a teacher sits before a stack of books trying to choose, sending up pleas to whatever gods that might be to guide her hand to the story that holds the potential for solace and connection and familiarity in this global time of crisis, fear, and loneliness. The brother and sister silently step into the classroom, hovering too near each other, craving connection, the only two bodies in the room allowed to remain closer than six feet, a small but potent gift. Four huge brown eyes lift and move slowly around the room. Two small bodies remaining perfectly still, skin prickling in the presence of so many other people, public school for the first time ever. The teacher explains how to combine simple sentences from eight feet away. The brother and sister hide their elegant grasp of English at all costs; they are not yet ready to offer this new world their souls in words. After grammar, the teacher places a copy of the novel in front of them, one each, the story of a Filipino American boy. The brother and sister open the red cover and begin to read their own story, in reverse.

III. For years the custodian has walked these halls and rooms, righting the chaos that blooms every day from the crush of 1200 bodies jostling and learning in one small space. He has read love letters crumpled and carelessly dropped, scooped up printed essays slipped desperately late under classroom doors, washed the day’s remnants of lessons from silky whiteboards, swept the crumbs from hundreds of illicit snacks out from under hungry children’s chairs. He has always known more of the dark underbelly of this place than most. Now he hides in the shadowed hush of the storage closet, surrounded by chemicals and latex gloves and a new addition, ‘the fogger,’ and fights tears no one would believe could possibly leak from his eyes, wipes them away with his massive strong hands, callouses catching in the folds of his eyes—hands now expected to hold and protect the health of 1200 bodies that still write love letters and late essays, that still sneak snacks under cover of masks when the teacher isn’t looking.

IV. He survived, that’s what he can say. The nights of screams and carefully aimed fists into the soft parts of the body, always (or almost always) under clothes so as not to be seen. Constantly moving, often cold, hunger too familiar. During court the judge said you deserved better from your parents. His abuela tried not to cry as her eyes darted from the judge to the translator and back in a frantic attempt to show respect where it was demanded. Now there are papers showing he belongs to this home where there is always food and blankets and heat; this will take some getting used to. When he gets sick, and then his abuela gets sick, and they have to move his Papa to Tia’s house because he is old and has diabetes, the boy stops going to school. He tries to learn to make soup, listening all the while to his abuela’s harsh coughing in the other room, fear in his stomach like an old friend. His teachers lament his lack of motivation to learn, and the red flashing number on the answering machine gets higher every day, the school attendance officer leaving orders in English that only he can understand. He tells his abuela not to worry, that they are only calling to make sure she is okay, that all is well. He turns back to the soup pot and stirs. He hums Las Mañanitas as he stirs; he is 14 tomorrow.

V. She is the only one in her family who has ever been any good at school, her brother tells her. Last year he hid in their small apartment for two months until the school gave up trying to find him, though they must not have tried very hard since 1401 Creek Street is right next door, on the same side of the street, even. All day long they hear the bells ring each hour and they know not to try to drive out of their parking lot at 8am or 2:30 for fear of being stuck in a throng of teens walking home. Her brother really used to be someone, running in a gang on the streets of Honolulu, and before that their island in Malaysia. Every hat he owned was red, riding atop his long black braid; he always had rolls of hundreds in a drawer by his bed, and those guns might have been dangerous, but only for others—they made her feel safe. Now, every morning in the dark, she lightly steps over the sleeping bodies on her way out the door, pulling it shut in silence, walking next door under the weight of a backpack filled with papers covered in her neat, tiny handwriting. He put a twenty dollar bill she hasn’t found yet in her jacket pocket. Briefly, her skin remembers the island air, warm and wet and heavy. She will be someone, too.

VI. Today in class the children remind the teacher of puppies, talking over each other and jostling each other and laughing. Masks slip down from noses, one girl unknowingly pulls her mask off as she excitedly explains to everyone that she heard a news article that was just like what happened in the book. The classroom door is open, and in the hallway a group of students jog past as they laugh and high five, another teacher hurrying behind them trying to catch up; he peeks into the classroom and his eyes crinkle above his 49ers mask, the new signal for smile. The sun slips up into the windows like a kiss.

VII. This morning she has a serious talk with herself in the mirror. You must hold everything in your two hands; you must make them big enough to carry it all. Your spine must become the pillar and not bend or break. Your arms and shoulders, she explains, are now the fulcrum, slanting slowly to one side and then the next as the weight piles on; your hands are the pans that can drop nothing, nothing do you hear me. You are the scale of the world. Sick parents, sick students, sick friends; “Guidance.” Teach them English they can use, wash their desks and tables and chairs, listen for hoarseness or a stuffy nose, look for signs of fever. Hug them and then wash your hands. Wait, don’t hug them, ever. Move your mom out for her own safety. Say goodbye to your partner until…after all this is over. Test every week. Briefly glance at the bowls you made from old magazine pages, back in March. Smash one. Tell your yoga mat to fuck off. Then tell it you’re sorry. Try to write.

###

Dr. Robbin Jack is a high school ELD and English teacher in northern California. She currently teaches at a public high school in a hybrid model with students in person two days per week, and online for three. Her passion is building school systems that acknowledge and then dismantle opportunity gaps for kids. She has been a teacher in some form for 20 years.

Dr. Robbin Jack is a high school ELD and English teacher in northern California. She currently teaches at a public high school in a hybrid model with students in person two days per week, and online for three. Her passion is building school systems that acknowledge and then dismantle opportunity gaps for kids. She has been a teacher in some form for 20 years.

*identifiers have been intentionally obscured.

Additional Resources:

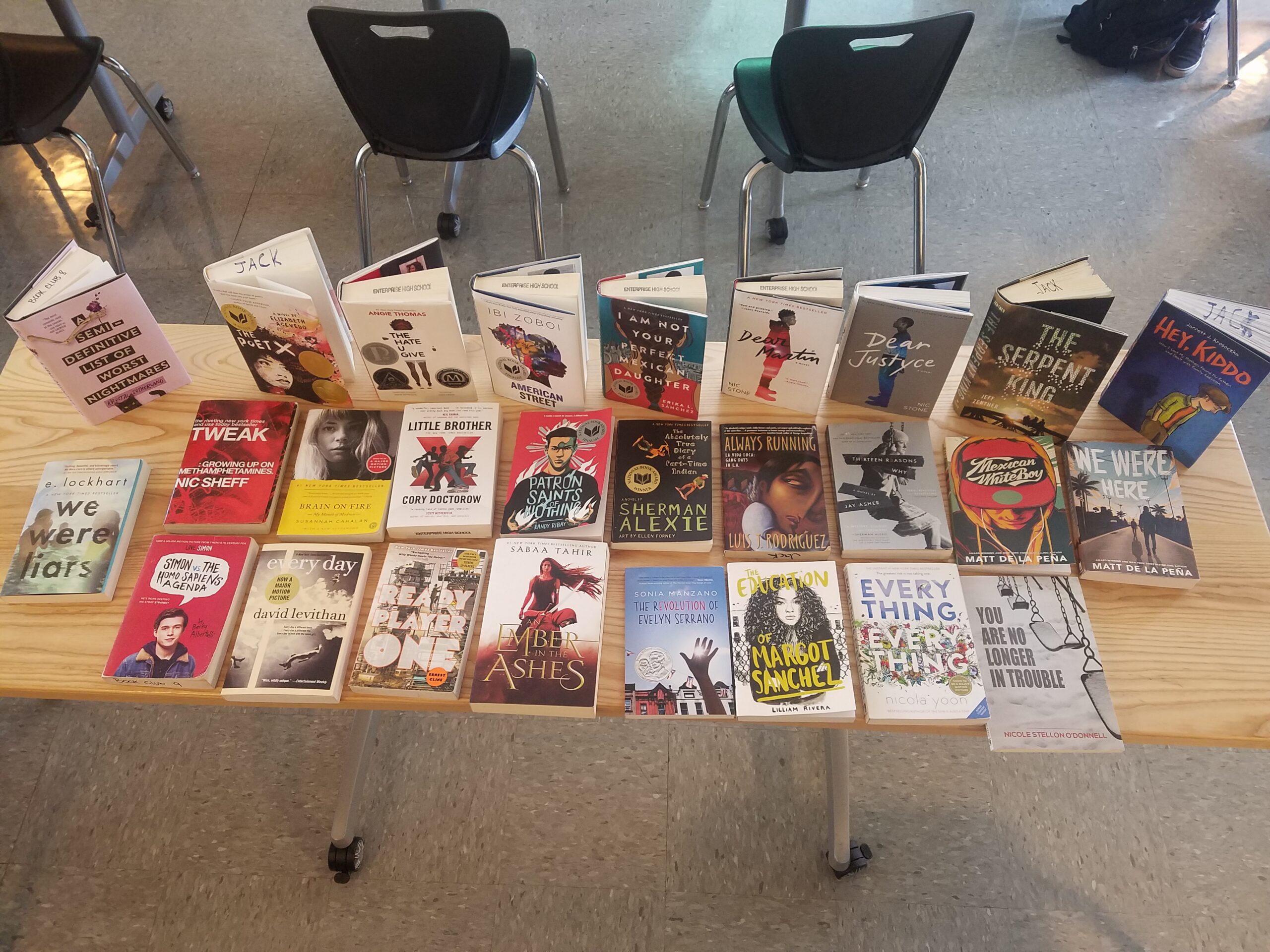

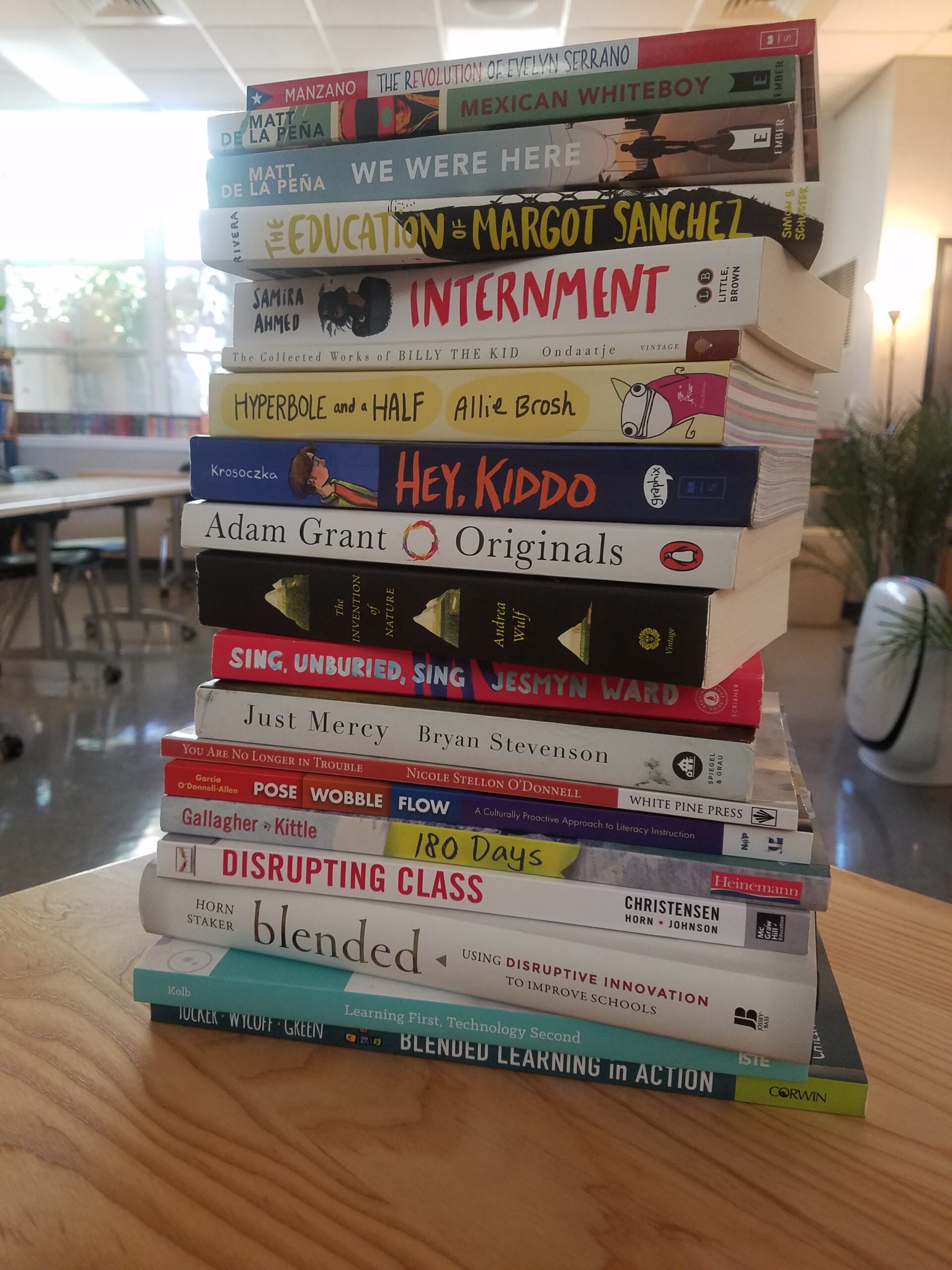

Readings referenced: Patron Saints of Nothing by Randy Ribay

- The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo

- I am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter by Erika L. Sánchez

- American Street by Ibi Zoboi

- Dear Martin by Nic Stone

- Internment by Samira Ahmed

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

- On the Come Up by Angie Thomas

- The Revolution of Evelyn Serrano by Sonia Manzano

- Mexican Whiteboy by Matt de la Pena

- We Were Here by Matt de la Pena

- The Education of Margot Sánchez by Lilliam Rivera

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, Ellen Forney (Illustrator)