Dispatches: Last Names and Street Names by Kendall M. Smith

Welcome to NCWP Dispatches.

How do we chronicle our days in a time that resists narrative? Like living through a long body of paragraphs, by the time we get to the conclusion, the introduction has changed. The memory of March is a distant cousin to the reality of August. And so we write missives: a memo, a letter to an old friend, a late night text, a doodle in the margins. Or perhaps a recipe, a rant, or an unsent email draft–forms that hold the capacity for uncertainty, story spaces already ceded to unknowing. In other words, the ephemera of this moment. With this in mind, this summer, the Northern California Writing Project hosted a space for a group of teacher consultants to write weekly, tracking their experience, observations, and process as they navigated the transition between the initial pandemic response in the spring to the impending, more-intentional classroom spaces created for fall. We called them Dispatches. Representing a range of grade levels, teaching contexts, and expertise, these educators created a writing community where deep dives into anti-racist pedagogy wove through questions and concerns about teaching communities, daily writing practice and illustrated mini essays resonated with one another, and over time the fullness of our experience came into focus.

Kitchen tables are now recording studios. Entire worlds are offered and built through the laptop’s persistent eye. Never before has the classroom felt at once so public, and so private, siloed in our homes or offices, away from students, colleagues, and campuses, trusting, hoping, our videos, documents, and discussions are finding their destination. As we stretch, week by week, into a school year like no other, we offer you the Dispatches from this summer’s writing, revised and expanded to include the ever-evolving challenges of teaching and learning, right now.

–Sarah Pape, NCWP teacher consultant and Dispatches coordinator

Last Names and Street Names by Kendall M. Smith

Teaching during a pandemic has not been easy. Contrary to popular and misguided belief, this has not been more time off or an extended summer. Instead, this has been perhaps one of the most emotionally charged years I have experienced. I’ve noticed that the lack of control has amplified my frustrations, especially towards those who misjudge our students. Lazy. Disengaged. Unmotivated. These are just some of the labels I’ve encountered as we made the switch from in person to distance learning. Labels in general do not sit well with me, and while the chorus of critics has grown loud, I’ve started to question why I put up with these kinds of judgements in “normal,” pre-pandemic times. Those with the loudest voices are strangers to our community—haven’t lived where I have lived, where my friends have lived, where our students currently live.

I grew up on Cypress Street (and South Lassen and Elm, but that’s a story for another day), west of the train tracks, one block south of the middle school along Interstate 5. When I close my eyes, I see the retired Marine posting the flag every morning. I see the stop sign on the corner where my 7th grade boyfriend innocently kissed me for the first time. I see my Mema’s yellow house where visiting is best done in the front yard with cocktails in hand.

Where I’m from, people are more connected than they’d think. All you need is a map of our town where just over 6,000 people are scattered over approximately 2.84 square miles. As kids, my pal Olivia and I could bike the perimeter in an afternoon.

There are several pockets of Willows, each with its own presence. The east side of the tracks is different. On the east side, streets are named sequentially–First, Second, Third. When I pull up my students’ addresses and I see these numbered streets, I understand something many of my colleagues might not: they haven’t seen the shattered glass in the gutters, the overgrown yards run by feral cats, the sheets that hang in the windows as curtains, or the old sheds in the alleyways that have been converted into houses with ten family members cramped inside.

When I pull addresses and see the streets named Crestwood, Baywood, Sherwood, or Glenwood (also known as “driftwood,”) I remember how during the winter rains, that these houses will take a hit from the flooding should they return. However, the names that mean the most to me have nothing to do with family pedigree. Instead they have everything to do with geography: avenues, streets, and county roads.

When I pull addresses and see the streets named Crestwood, Baywood, Sherwood, or Glenwood (also known as “driftwood,”) I remember how during the winter rains, that these houses will take a hit from the flooding should they return. However, the names that mean the most to me have nothing to do with family pedigree. Instead they have everything to do with geography: avenues, streets, and county roads.

In Willows, one’s last name is social capital, and I mean no disrespect when I say this, but I do acknowledge that the pendulum swings both ways: one name might inspire a warm smile, while another summons a long look-you-up-and-down scowl followed by “bless your heart” as a response. We all know this to be the most kind way to say nobody cares.

Thanks to the union of the Spooner and Carriere families I come from a long line of rice and walnut farmers; the Carriere family in particular has five generations of farmers in its lineage. In Willows, this is the norm. This points to another norm upon meeting new people is to ask, “Now who are you related to?” or “What’s your last name?” Depending on our answers we come to varying levels of positive and negative perceptions of one another. It’s a Willows thing…

Surely, street names and last names are not the only thing that define our lived experience. While I can conjure up an image of someone’s background, I recognize how my judgments can be completely off base. And just like our video boxes on Zoom, these names never show us the whole picture. As we continue learning and teaching during this pandemic I think having this in mind will be especially important. What I’m left with now are dozens of black screens and some first and last names…that’s it.

I knew that through this new teaching model I would be in the homes of my students, but I did not consider how their homes would also be brought into my classroom. Piecing together names with street names has reminded me of how much school is an escape for so many. While taking a colleague on a tour of Willows, we drove through the parking lot of the biggest apartment complex in town. I explained how one of my students moved out because it was getting too dangerous. I used to live in apartments just like those ones. I remember feeling glad to leave them every morning to eat breakfast at my Mema’s house and then head off to school. Though decades separate me from those stacked apartments and my own family’s struggles, the fact that I’m a teacher here in this same place helps me see how much can change with time. Yet, I still wonder how is it possible to feel that out of touch from that life now? I teeter between guilt and gratitude. How can I use both to serve my students?

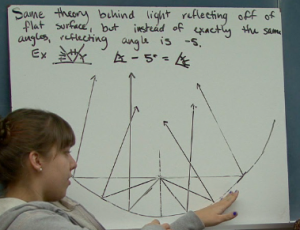

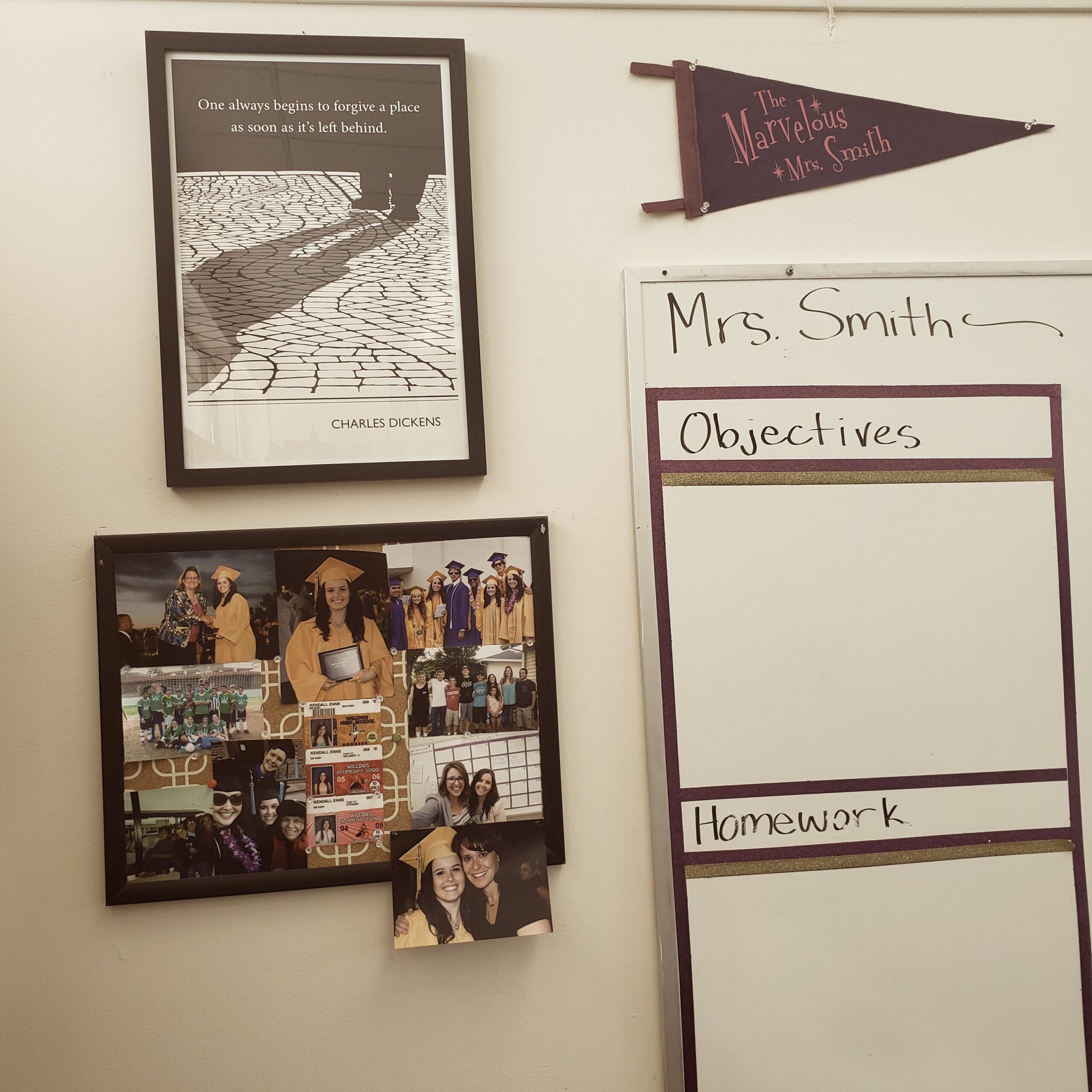

The other day I popped into Willows’ local coffee shop, and some students recognized me and this allowed me to feel a moment of comfort. “Mrs. Smith?!” two young ladies exclaimed my name with surprise and excitement! I felt my smile spread across my face as I gleefully replied, “YES!” We hugged, we laughed, we chatted and said our see you laters. Thanks to moments like these I’ve come to appreciate putting a face to a name more than ever. I’ve also come to appreciate whatever students allow me to see. I know there have been other students who have seen me, knowing fully well who I am, but choosing to remain a mystery. As much as I want students to turn their cameras on, honoring their boundaries is worth the wait.

Here I sit in my spare room writing this–four weeks into teaching via distance learning and yet I still feel so close to my students. They can’t help what their last name is nor can they help what street they live on, but they can define their experiences using their own perceptions as the final word. Each of them is worthy of the opportunity to exceed the superficial judgments we (myself included) place on them.

I’m a Spooner, I’m a Carriere, I’m a Taylor, I’m a Carney, I’m an Enns, I’m a Smith. I’m Cypress, Elm, and South Lassen Street. Growing up I did not appreciate the stigma that came with these names. Now the stigma has evolved into a strength because I’ve come to understand the weight of last names and street names. We have forgotten the complexity of students’ lives because they are no longer physically there in the room with us. The Willows High School student I once was would not have shown my face and I would have hesitated to speak out, but I would have yearned to be seen and understood. As teachers, it’s our job to find another way to make every effort to reach our students. Because all we have are names on a black screen, we should feel compelled to inquire more about the unseen.

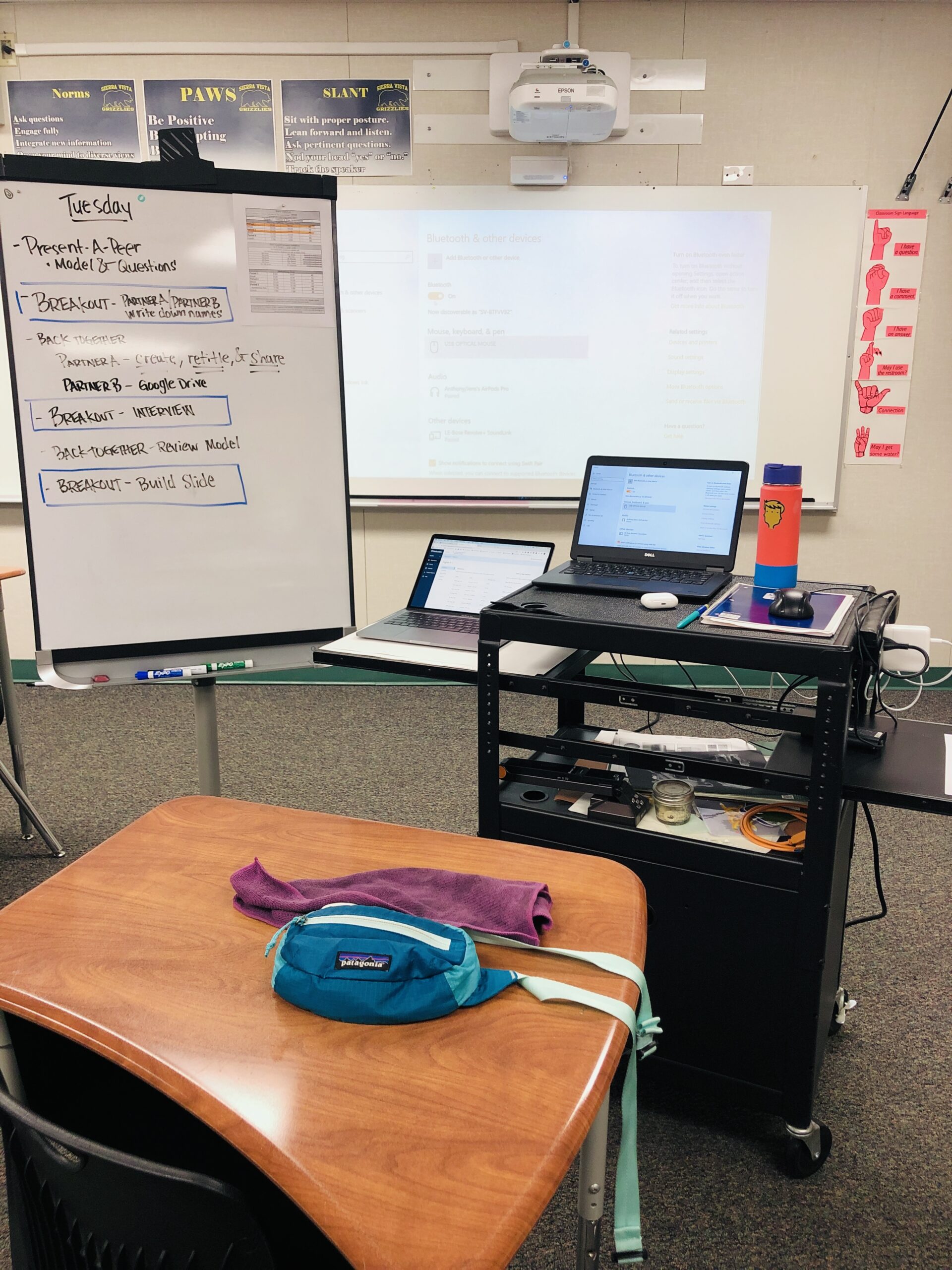

Kendall Smith is a high school English teacher at Willows High School. She serves as an advisor for the Interact Club, co-advisor for the Sophomore Class, and aspires to bring Mock Trial to her site this upcoming school year. She completed her Master’s in Education through the Residency in Secondary Education (RiSE) Program at Chico State in 2017. Prior to that, she was an English tutor for Burmese refugees in Chiang Mai while studying abroad in Thailand as a Gilman International Scholarship recipient. The travel bug has since then inspired her adventures throughout Southeast Asia and Australia. In January, she and her husband were married on the island of Koh Tao joined by close friends. During the summer she teaches for the Upward Bound Program at California State University, Chico where she helps students write personal statements for college admission. In her spare time, she enjoys plotting her next adventure, paddling boarding with her husband, kickboxing with friends, and studying Vedic meditation with some yoga in between.

Kendall Smith is a high school English teacher at Willows High School. She serves as an advisor for the Interact Club, co-advisor for the Sophomore Class, and aspires to bring Mock Trial to her site this upcoming school year. She completed her Master’s in Education through the Residency in Secondary Education (RiSE) Program at Chico State in 2017. Prior to that, she was an English tutor for Burmese refugees in Chiang Mai while studying abroad in Thailand as a Gilman International Scholarship recipient. The travel bug has since then inspired her adventures throughout Southeast Asia and Australia. In January, she and her husband were married on the island of Koh Tao joined by close friends. During the summer she teaches for the Upward Bound Program at California State University, Chico where she helps students write personal statements for college admission. In her spare time, she enjoys plotting her next adventure, paddling boarding with her husband, kickboxing with friends, and studying Vedic meditation with some yoga in between.

Additional Resources

“Connecting Rural Educators: Professional Development Goes Digital” by Kim Jaxon and Amanda VonKleist

“Connecting Rural Educators: Professional Development Goes Digital” by Kim Jaxon and Amanda VonKleist

Kim Jaxon, director of the Northern California Writing Project, shares this post (originally written for the Connected Learning Alliance) about how her Writing Project site has experimented with using digital spaces to provide greater access to professional development for rural educators.

“The organization’s mission is to build sustainable rural communities through a keen focus on place, teachers, and philanthropy. RSC’s mission is realized through four signature efforts: The Place Network, Rural Teacher Corps, Grants in Place, and Impact Philanthropy.”

“Schools serving communities with high rates of poverty face the profound challenge of meeting the needs of students who are often exposed to significant family and environmental stressors and trauma. Classroom staff are vital members of school communities who often work closely with students with the highest needs, but they are typically not provided with professional development opportunities to develop skills for social–emotional learning intervention.”

Antero Garcia and Elizabeth Dutro’s “Electing to Heal: Trauma, Healing and Politics in the Classroom”

“Abstract: Among the lessons that emerged after the recent presidential election is a recognition that teachers are generally not prepared to address the intersections of healing, politics, and emotion in classrooms. Drawing on research, the voices of teachers, and our experiences over this past year, we call for more expansive conversations among English educators across perspectives concerned with creating safe, relational, anti-oppressive classrooms.”