Dispatches: Toward What Aim? – Reflections on Respectability and “Language of Power” by Anthony Miranda

Welcome to NCWP Dispatches.

How do we chronicle our days in a time that resists narrative? Like living through a long body of paragraphs, by the time we get to the conclusion, the introduction has changed. The memory of March is a distant cousin to the reality of August. And so we write missives: a memo, a letter to an old friend, a late night text, a doodle in the margins. Or perhaps a recipe, a rant, or an unsent email draft–forms that hold the capacity for uncertainty, story spaces already ceded to unknowing. In other words, the ephemera of this moment. With this in mind, this summer, the Northern California Writing Project hosted a space for a group of teacher consultants to write weekly, tracking their experience, observations, and process as they navigated the transition between the initial pandemic response in the spring to the impending, more-intentional classroom spaces created for fall. We called them Dispatches. Representing a range of grade levels, teaching contexts, and expertise, these educators created a writing community where deep dives into anti-racist pedagogy wove through questions and concerns about teaching communities, daily writing practice and illustrated mini essays resonated with one another, and over time the fullness of our experience came into focus.

Kitchen tables are now recording studios. Entire worlds are offered and built through the laptop’s persistent eye. Never before has the classroom felt at once so public, and so private, siloed in our homes or offices, away from students, colleagues, and campuses, trusting, hoping, our videos, documents, and discussions are finding their destination. As we stretch, week by week, into a school year like no other, we offer you the Dispatches from this summer’s writing, revised and expanded to include the ever-evolving challenges of teaching and learning, right now.

–Sarah Pape, NCWP teacher consultant and Dispatches coordinator

Toward What Aim? – Reflections on Respectability and “Language of Power” by Anthony Miranda

Toward What Aim? – Reflections on Respectability and “Language of Power” by Anthony Miranda

It was a Wednesday afternoon in early-August, and my small department team and I were meeting at the start of the new school year. We’ve been working closely together for the last two or three years, co-teaching and mentoring across grade levels. I was thinking aloud, and as I spoke, I realized something that might fundamentally change my approach to teaching.

“So,” I said folding a neon pink Post It into a triangular shape, “I’m just thinking about this book I read and wondering whether the premise I’ve been operating on is wrong.” I pressed my finger down and creased the edges.

“I mean, how can I say that I want to center the margins and at the same teach academic language as the language of power?” I teed up the Post It and flicked it into my empty classroom.

My eyes moved to the small rectangles that held pixelated versions of my department team. “I’m just wondering about an approach that validates and affirms home language within a classroom where most assignments and measures of success are grounded in language that looks and sounds a lot like white, middle-class cultural and linguistic practices.” The faces on the screen considered this in silence.

For years now, I’ve been seeking to equip students from marginalized backgrounds with the ability to “code-switch” or utilize White Mainstream English in an effort to have students appropriate the linguistic capital necessary to navigate and game the social contexts that call for that language to be used. Chasing that idea has become my rationalization for staying in this profession, for showing up each August and rolling the stone up the hill once more.

I began applying this approach in my classroom while teaching in a small rural Northern California school serving a student population that was predominantly Latinx and overwhelmingly socioeconomically disadvantaged. After two years, I moved into a Curriculum Support Provider role within that district where I used this code-switching philosophy to shape and direct a district-wide writing initiative. Now, for the last four years, I’ve been teaching 7th and 8th English at a K-8 school near the Bay Area. When I became Department Chair last year, this “code-switching” philosophy became a central idea guiding our small English department.

However, this summer I was introduced to Dr. Baker-Bell’s Linguistic Justice, and her analysis of language and literacy pedagogies that fundamentally challenges this notion of “code switching” and has tied my thinking in the type of knot that demands untangling and unravelling. Her words forced me to reckon more directly with the fact that centering the margins entails de-centering whiteness.

Since I first entered the classroom, my dogged eared and margin-scrawled copy of Sharokkie Hollie’s Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Pedagogy has been central to my practice. I’ve talked it up so much that my school has adopted it as our 2020 Teacher Text. I’ve been adhering to this pedagogy with the rationale that I am teaching students the “game.” to play the “game,” and to change the “game.” In the text, Hollie directs teachers to Validate, Affirm, Build, and Bridge (V.A.B.B.) students’ linguistic resources they bring into schools. For Hollie, “Bridging is providing the academic and social skills students will need to have success beyond your classroom…Bridging is evident when your students demonstrate that they are able to successfully navigate school and mainstream culture.” I’ve implemented strategies from Hollie but also employed this framework as an evaluative lens for whether to incorporate new strategies by asking, will they help students bridge?

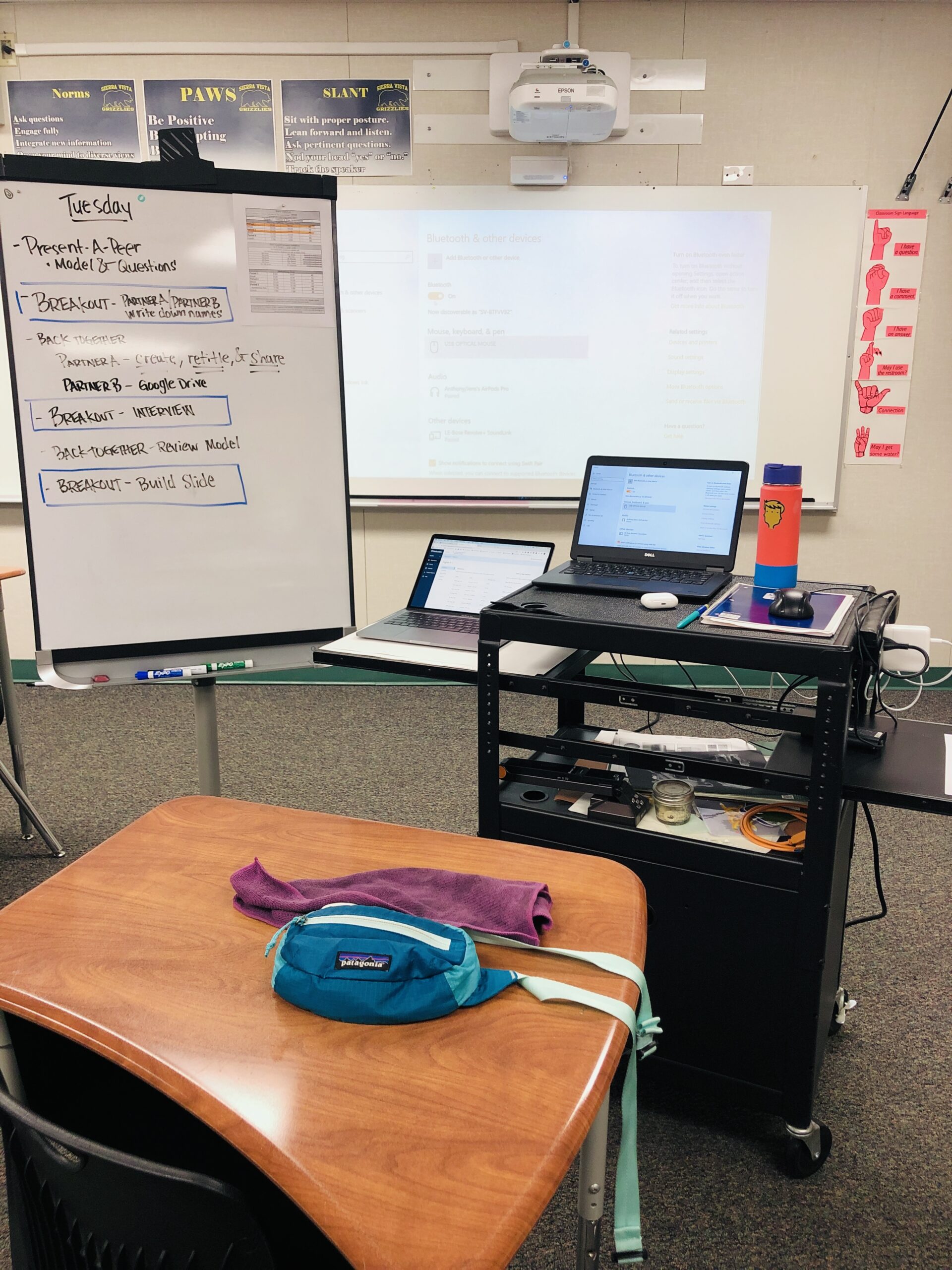

At this point in my career, my classroom walls are covered in anchor charts with academic conversation sentence starters. When Brianna shares a brilliant idea about her Literature Circle book with the class, I respond, “I love that idea, but, Bri, can we say it in a way that uses the sentence stems?” She complies and I follow up, “Hey, what a powerful idea, can someone rephase and build on,” I alternate stacking clenched fists, “using their Academic Conversation placemat?” Then we move to developing our ideas through color-coded sentence stems for argumentative writing. Administration might enter my 3rd period and silently view the lesson. Before leaving they drop a note on my desk, “What a language-rich classroom!” The code-switching approach has certainly been effective in getting my students to “play the game” but despite my V.A.B.B.ing, the “game” persists unchanged.

In Linguistic Justice, Dr. Baker-Bell contends that frameworks like Hollie’s would fit into what she terms Respectability Language Pedagogies, which, “refer to approaches that view racially and linguistically marginalized students’ language practices as valid and equal yet instruct these students to use White Mainstream English to avoid the negative stereotypes that are associated with their linguistic and racial backgrounds by appearing ‘respectable’” (29).

But Baker-Bell, “Rejects the myth that the same language [White Mainstream English] and language education [that] have been used to oppress Black students can empower them.” In response to this “code-switching” framework, Baker-Bell points out that “I can’t breathe” was a grammatically sound and situationally appropriate statement that should have ended in Eric Garner navigating the social context in which he was situated.

Using Hollie’s framework, my goal has been to validate students’ “home language.” I’ve tried to communicate the value of the language and literacy practices that take place in the discourse communities that students participate in outside of school. But I’m wondering also about the impact of following talk of validating “home language” with privileging “academic language” within lessons through the use of sentence stems for academic conversations that are deemed “situationally appropriate” within the context of the classroom. The sum of this incoherence seems to equate to actually showing that those language and literacy practices from outside of the classroom that I just told students are valuable, in fact, have little to no value in this academic space. What Baker-Bell says makes this approach, and others like it, “dangerous and harmful to Black students [i]s they teach them to be ignorant of anti-black linguistic racism and bow down to it rather than work to dismantle it.”

Admittedly, I’ve been reflective of the mental gymnastics I’ve been performing to rationalize Hollie’s approach for some time, so a few years ago I began calling Academic English “the language of power” in my practice to try and acknowledge the asymmetrical power relationship between it and other forms. But without sustained explanation and inquiry into the construction of the “language of power” with students, it felt performative, at best.

This has been the problem I’ve been unable to shake, and that Baker-Bell so powerfully articulates, which is that code switching and bridging fails to develop in students a critical consciousness of the underlying reasons why Academic Language in the context of schooling has come to be deemed “situationally appropriate.” For Baker-Bell, to acknowledge the ways in which Academic Language is also a reflection of white, middle class cultural and linguistic values, “would be an effort in Black linguistic consciousness-raising that helps Black students heal and overcome internalized Anti-Black Linguistic Racism.”

As an educator seeking to center the margins, I want to be able to move from a focus on teaching the game and instead to engage in the sort of reflective analysis and instructional shifts that might decenter whiteness and dismantle the game. I’m beginning this sort of reflection by taking stock of what is shaping the language demands in my classrooms and naming the ideas and frameworks that influence my planning, design, instruction, grading and conceptions of student success. I’m starting with the end in mind and asking:

– Does success in my classroom mean students have to “pull off” an identity that uses language and literacy practices that share affinities with White Mainstream English?

– What are the end products I am accepting as proof of mastery of standards?

– Which standards am I prioritizing when building lessons, administering formative assessments, and developing rubrics? What ideological baggage do these standards show up to the door carrying?

– In my gradebook, which assignments are weighted more heavily and is there a particular register those assignments favor?

– When using mentor texts within a genre study unit, how might I incorporate discussions of the histories of anti-black linguistic racism within those particular genres?

– What are the opportunities that allow students to utilize non-academic literacies in my classrooms? Are these opportunities regarded as essential within the unit or creating superficial engagement and buy in?

– In what ways are my definitions of rigor, participation, and proficiency dismantling or maintaining While Linguistic Hegemony?

Through emails, texts, and back channel chats, my department team and I have been working through these ideas. We are now entering our 8th week of distance learning. We are still navigating student technology access and issues. We are still working to understand and teach new learning management systems. But as white (and white passing) folks, we are very purposefully trying to grapple with the contradictions inherent in the aims of schooling and an education for social and racial justice.

We ponder, wonder, and challenge ideas about our complicity and agency within this system that is simultaneously oppressive and brimming with emancipatory potential. Each day of each week we enter our classrooms, log into our Zoom sessions, and try once again to turn the tangle straight.

Anthony Miranda is a 7th grade English teacher and department chair. His interests are in exploring ways of using language and literacy that enable students to recognize and navigate schooling as a complex institution, in designing connections between content and civic participation, and in ongoing, critical reflection of how teachers negotiate the tension between schooling, as an instrument of oppression, and education, as an emancipatory practice. Prior to teaching only English, he taught 7th and 8th grade English and History. He participated in the UC, Berkeley History-Social Science Project’s Teacher Research Group that focused on making explicit to students the historical thinking skills necessary for evaluating and more fully understanding historical narratives. He is also interested in exploring and evaluating language and literacy initiatives that support students from non-dominant backgrounds. As a Curriculum Support Provider for ELA/ELD, and through participation in site-based teams and committees, he has explored how organizational theories of change and models of implementation can leverage teacher expertise and include their voice in the process of change. Outside of the classroom, he can be found with his wife at museums and art galleries, hiking and biking, or making the rounds to the local breweries.

Anthony Miranda is a 7th grade English teacher and department chair. His interests are in exploring ways of using language and literacy that enable students to recognize and navigate schooling as a complex institution, in designing connections between content and civic participation, and in ongoing, critical reflection of how teachers negotiate the tension between schooling, as an instrument of oppression, and education, as an emancipatory practice. Prior to teaching only English, he taught 7th and 8th grade English and History. He participated in the UC, Berkeley History-Social Science Project’s Teacher Research Group that focused on making explicit to students the historical thinking skills necessary for evaluating and more fully understanding historical narratives. He is also interested in exploring and evaluating language and literacy initiatives that support students from non-dominant backgrounds. As a Curriculum Support Provider for ELA/ELD, and through participation in site-based teams and committees, he has explored how organizational theories of change and models of implementation can leverage teacher expertise and include their voice in the process of change. Outside of the classroom, he can be found with his wife at museums and art galleries, hiking and biking, or making the rounds to the local breweries.

Additional Resources:

Book trailer for Linguistic Justice

Geneva Smitherman’s “Raciolinguistics, “Mis-Education,” and Language Arts Teaching in the 21st Century”

“This historical moment calls for language arts teachers to be bold and courageous; to talk more and teach more about language and/as race—i.e., raciolinguistics—and to recognize students’ right to their own language as well as they right to choose the pronoun which they want you to use when you refer to or address them. Language arts teachers are ideally positioned to exert leadership in the rejection of English-only and Standard English-only policies and practices, with all their negative consequences for our 2lst Century multilingual, multicultural students” (10).

bell hooks Engaged Pedagogy, chapter 1 from Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom

“Progressive professors working to transform the curriculum so that it does not reflect biases or reinforce systems of domination are most often the individuals willing to take the risks that engaged pedagogy requires and to make their teaching practices a site of resistance” (21).

Drs. Carla España and Luz Yadira Herrera’s En Comunidad: Lessons for Centering the Voices and Experiences of Bilingual Latinx Students

“En Comunidad brings bilingual Latinx students’ perspectives to the center of our classrooms. Its culturally and linguistically sustaining lessons begin with a study of language practices in students’ lives and texts, helping both children and teachers think about their ideas on language. These lessons then lay out a path for students’ and families’ storytelling, a critical analysis of historical narratives impacting current realities, ways to develop a social justice stance, and the use of poetry in sustaining the community.”