Dispatches: Course Design for the Now Times by Kim Jaxon

Welcome to NCWP Dispatches.

How do we chronicle our days in a time that resists narrative? Like living through a long body of paragraphs, by the time we get to the conclusion, the introduction has changed. The memory of March is a distant cousin to the reality of August. And so we write missives: a memo, a letter to an old friend, a late night text, a doodle in the margins. Or perhaps a recipe, a rant, or an unsent email draft–forms that hold the capacity for uncertainty, story spaces already ceded to unknowing. In other words, the ephemera of this moment. With this in mind, this summer, the Northern California Writing Project hosted a space for a group of teacher consultants to write weekly, tracking their experience, observations, and process as they navigated the transition between the initial pandemic response in the spring to the impending, more-intentional classroom spaces created for fall. We called them Dispatches. Representing a range of grade levels, teaching contexts, and expertise, these educators created a writing community where deep dives into anti-racist pedagogy wove through questions and concerns about teaching communities, daily writing practice and illustrated mini essays resonated with one another, and over time the fullness of our experience came into focus.

Kitchen tables are now recording studios. Entire worlds are offered and built through the laptop’s persistent eye. Never before has the classroom felt at once so public, and so private, siloed in our homes or offices, away from students, colleagues, and campuses, trusting, hoping, our videos, documents, and discussions are finding their destination. As we stretch, week by week, into a school year like no other, we offer you the Dispatches from this summer’s writing, revised and expanded to include the ever-evolving challenges of teaching and learning, right now.

–Sarah Pape, NCWP teacher consultant and Dispatches coordinator

Course Design for the Now Times by Kim Jaxon

Course Design for the Now Times by Kim Jaxon

Like many of my colleagues who think about digital pedagogy, I’ve been fielding a lot of questions from fellow educators as we shift to online teaching. Every educator I know is trying to get this moment right, to do our best to support learners. Universities and school districts are scrambling to support faculty and students as well, all with the best intentions. My own intention with this piece is to share course design practices and resources that might serve as alternatives to the primarily tool based, EdTech, approach. My fear: we’re worrying so much about solving problems of schooling that we’re forgetting to solve problems in our disciplines and in the world. More concerning, we’re allowing EdTech to rule our choices. Lots of companies are ready to sell us solutions for problems we didn’t know we had. At stake are our students (and teachers) and the ways their bodies are being controlled in the name of learning. We need to stop the outcomes, rubric, template, surveillance, plug in, packaged courses, frenzy.

I offer an approach to course design that moves away from “how do I take attendance” and toward “how do I support a newcomer to my community?” The suggestions are also guided by the most frequently asked questions I receive from faculty. Keep in mind, I never leave a class thinking “nailed it!” I humbly offer a process that I am constantly reflecting upon and revising.

One way to begin: a brainstorming session to understand your discipline

A few years ago, I was fortunate enough to join a small group of international educators to think about professional development support for faculty who wanted to rethink digital pedagogy. We created an open site, Connected Courses, which you can access for resources: readings, example activities, webinars for course design. When we created the first sessions, we began by asking educators to consider the “why” of their courses; unlike a lot of course design, we didn’t start with content and outcomes (which are strange anyway: the learner should drive the learning outcomes, but that’s for another piece). We started with the why: why should students join our disciplines? Mike Wesch, a cultural anthropologist at Kansas State University, offered a model for thinking about the “why” by starting with our disciplinary identities:

As I contemplated the “real why” of my course further, I soon recognized that anthropology was not a bunch of content and bold faced terms that can be highlighted in a text book, but was instead a way of looking at the world. Actually, that is not quite right. It is not just a way of looking at the world. It is a way of being in the world. To underscore the difference, consider that it is one thing to be able to give a definition of cultural relativism (perhaps the most bold-faced of bold-faced terms in anthropology which means “cultural norms and values derive their meaning within a specific social context”) or even to apply it to some specific phenomenon, but it is quite another to fully incorporate that understanding and recognize yourself as a culturally and temporally bounded entity mired in cultural biases and taken-for-granted assumptions that you can only attempt to transcend.

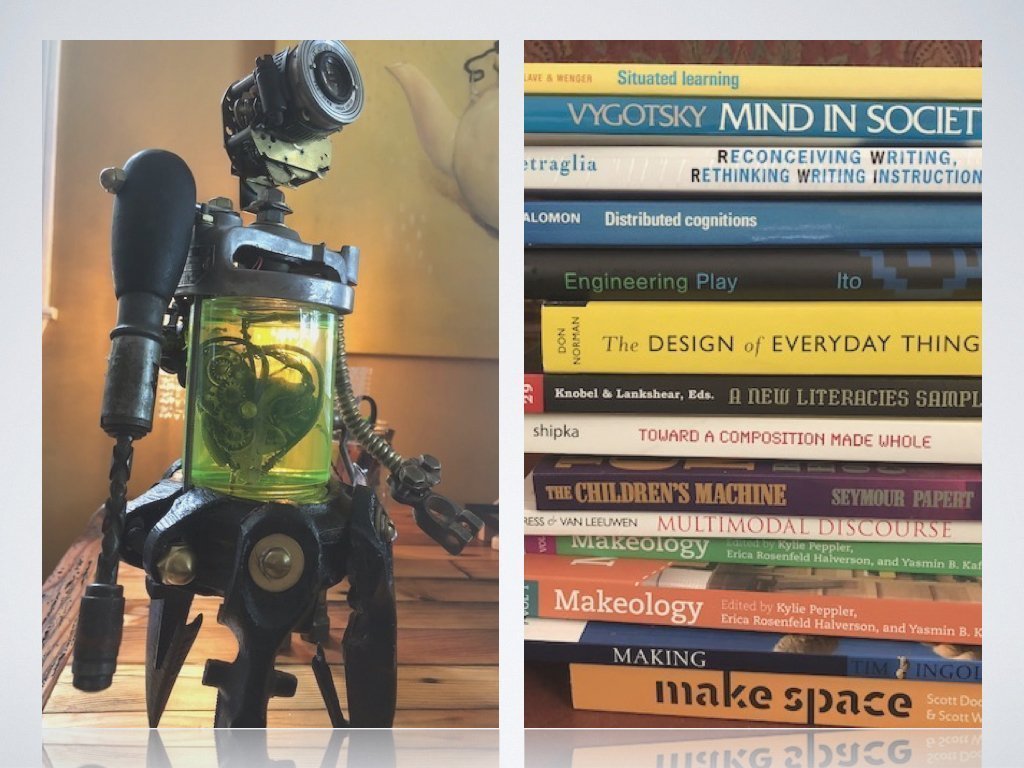

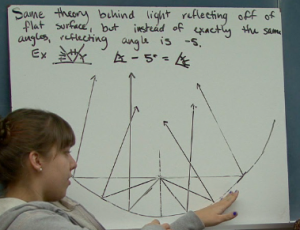

Once we come to understand that our disciplinary identities shape who we are and how we work, you start to notice these differences. For me, I remember vividly an early meeting with two science colleagues as we planned to research writing in science classes together. I watched them enter my office, arguing about a question related to light that had emerged in their co-taught class right before our meeting. Leslie (physics) and Irene (biology) had come to my office deep in conversation; they looked around, searching for a white board in my space to hash out the disagreement. They could not believe I didn’t have a whiteboard: doing science and talking about science without being able to draw representations of science is, well, sort of unheard of as I would come to understand. Even if I had had a whiteboard in my office on that day, as an English professor, it would more likely have been in use for to-do lists. Tools, even whiteboards, do not serve the same purpose across disciplines. And yet, EdTech would have us believe that there is one tool to rule them all.

My chemistry colleague, Lisa Ott, echoed these ideas this spring, as we were facing online teaching: “…you certainly can’t be a chemist without pouring some shit in a beaker and seeing what happens. It’s an experimental science.” Lisa spent part of this summer with chemistry colleagues thinking about how to solve the problem of being a chemist: “working on inquiry-based at-home analytical chemistry labs using microfluidic devices. We had so many discussions about what it means to be a chemist, different ways to teach students the practice of chemistry, alternative assessments– everything moving away from plug-and-chug and test, test, test. Everything moving toward playing in the places where chemists live.”

An activity to try:

An activity to try:

I invite faculty to take some time, even 15 minutes, to informally write about disciplinary identities and the “whys” of your field. Some prompts to consider:

- What does it mean to be an historian? An engineer? A poet? A political scientist?

- How do you move through the world and see the world (like Wesch describes above)? What questions guide your field?

- What are the tools of your discipline?

- What spaces do you inhabit online? For example, I’m on Twitter because all of the educators I collaborate with are on Twitter. Computer scientists occupy spaces in GitHub. None of my colleagues, or the ideas in my field, live in the LMS. I know for some of you, the answer would not be a digital space at all; it might be “in a creek” or “on a mountain” or “surrounded by cows.” In the now times, perhaps students can still set out for those spaces and use an online space to share offline learning.

- Why should students take your course or become _____ists?

Apply your brainstorming session above to course design:

- Ways of being: who are students invited to be in your course (beyond “a student”)? Do they have an opportunity to try out, even in failed attempts, what it means to be this kind of person? In art classes, for example, students are invited to gallery walks and critiques, mentored in ways of talking about art with other artists.

- Ways of working: What does it look like to do history or political science instead of learning about history or political science? How can you invite students to work in the ways your field works? What does informal writing look like in your field (email exchanges? Notes on paper? Chats in front of whiteboards?)? How might you break down formal assignments or projects into the “behind the scenes” parts? Which platforms or tools does your field use? Github, Adobe Illustrator, Google Docs? How do you collaborate with colleagues? Again, using DropBox, Google? Exchanging Word documents in email? What if you were leading a workshop with colleagues in your field: which tools would you use?

- Ways of situating: Where do your professional communities live online? For example, I point my students to the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and invite students to sign up for their newsletter. I request free copies of NCTE journals and hand those out to students. I point them to educators to follow on Twitter and introduce them to Instagram accounts like WeNeedDiverseBooks. In other words, I point them to where the fish are swimming in my field, toward the communities my students want to join. Where do your professional communities live or share informally?

I recognize the desire to limit the amount of platforms, tools, webspaces we are asking students to join or sign up for. This point is not trivial. But we are doing students a disservice, we are gatekeeping access, when we hide the communities they want to be a part of and only play in schooled platforms. Students do not need proficiency in learning how to use the LMS discussion board, the way to submit essays in TurnItIn, how to navigate a publisher’s textbook and quiz bank, and the worst, how to take a quiz while being proctored, and yet so much of their education is a series of lessons in schooled practices, not the rich practices of our fields. When people say students need a templated experience so they can more easily take our classes, I call BS. Students are already asked to use a ton of tools; how cool would it be if they were using tools that exist in the world, in their fields instead. Trust students; they are capable. They desperately need and want to play and learn for real. In fact, they may have an easier time navigating our disciplines when the spaces look different, not similar. The various spaces allow students to try on various identities: geographer, poet, chemist, sociologist… The LMS assumes they have one: a student.

tl;dr: who do students get to be in your classroom and what do students get to do in your classroom? Is the thing you’re asking students to do a thing that people do in your field? Is it a thing people do in the world outside of school? Carefully select any digital tool based on the answer to those questions. Ask yourself if your colleagues would recognize the tool. If you must, use the LMS for your syllabus and a calendar and then get students out of there and into the communities and spaces of your field.

One next step: building community and attention to noticing

By far, the question I am asked most frequently is about classroom community, stemming from the fear of its loss. For what it’s worth, here are some ways I intentionally design for community in online classes. Some of these ideas are no doubt things many of you are already doing:

- Surveys: A week or so before the semester starts, I send students a survey. I ask about their technology access and comfort, including some lists with choices of specific tools. Since I teach writing, I ask about their experiences and views with writing in their lives. I leave some open questions so they can share concerns or ask me questions. This semester, I’m asking how they would prefer to receive weekly updates: in announcements, in email, on our website, in an app like GroupMe. I’ll post updates in most of these places, but also create personalized ways to share information (a small group who chooses GroupMe and a group who chooses email, for example). I see this as a simple copy and paste issue that may make their life easier: they can opt-in to how they want to communicate. I send surveys about once a month to see how things are going in our class: I ask what is working, what is not, suggestions for adjustments, all anonymously.

- Videos: I record weekly videos to supplement the announcements. I try to do these outside, borrowing from Mike Wesch. He has a great YouTube series here you can subscribe to. I plan to level up this semester by trying out his “mixed tape” idea for weekly updates.

- First week and its importance: I see the first few weeks as crucial to community building. I start with the obvious: introductions.

- I use Currents (formerly G+ Communities) since students do not need a separate log-in; they can use our campus log-in since we have Google Suites. Since many of my students are future k-12 teachers, introducing them to the Google Suite of apps is important since most school districts use this platform. Everything we use is something they can try out to use in their own classrooms. For the introductions, I give them some choice of format: video, short writing, audio, a series of images. I model an introduction too.

- I comment as quickly as their introductions appear in the Currents community and make connections on their posts, often sharing a link to a book, a film, something connected to their interests that also connects to the ideas in our class.

- I email/communicate immediately on the first week and establish the weekly routines.

- I offer reading/writing activities and respond within days on that first week. They will keep doing fabulous work when they know someone is reading it and engaging with it. We think so much about student engagement, but do we demonstrate our own engagement with their ideas? Even in a face to face class, I never go over the syllabus on the first day: I use the first day to model the ways we will work all semester. If I hope they’ll talk to each other, read things, write things, make things, then we need to do that on day one; if I go over the syllabus, then that’s what I’ve just modeled as the most important thing. Go over the highlights of the syllabus another day or week. They can read it. The same goes for online: do the things the first week that you hope you’ll do together all semester .

Noticing and celebrating student work

- Review board: I’ve written about the use of a review board previously in articles about large course design. This passage from “Epic Learning…”

As an example of one structure that supports, and more importantly, makes noticeable, the scholarly work of students, I ask students to participate in a “Review Board.” Each workshop team sends a representative to meet with me for an hour outside of class time each week. The Review Board is responsible for reading the work of their peers and nominating a writer to be featured in class. We end up with nine featured writers — one from each workshop — and we pick a few to talk about in the large class. The review board’s job — back in the large class — is to present the writing, talk about why they think it represents some of the best thinking that week, pose questions to the featured writer about her choices, and celebrate their peers. I am always impressed by this small Review Board team: without prompting they will often ask “what was the purpose of the writing this week?” Or they will say, “we featured her work last week; we should make sure someone else is featured.” The students recognize that the writing is intentional and that we value the ideas from as many students as possible in our class. Each week, a new batch of scholars emerge and are highlighted in our space — and over time — we build a community where the students are noticed.

- Featured curators: In a few of my classes, I ask students to be responsible for noticing great ideas from our class and their peers. Everyone has a chance to curate ideas once: they are invited to review the work our class has produced that week and write a blog that highlights the work. You can see an example here. And again, since most of my students are future teachers, noticing interesting thinking from students is a practice I hope they try out.

- Ongoing amplification: I always use the weekly updates and reminders to amplify student ideas. I often mention students and their ideas/questions in the weekly videos. I include short passages from their work, awesome questions someone asked, “golden lines,” which are favorite sentences from each students’ writing that week. Sometimes I ask them to highlight a favorite sentence from a peer or from their own writing; they send these to me and I include them in the update.

A note about synchronous and asynchronous approaches to community: One response to a fear about the loss of community is an attempt to duplicate community through platforms like Zoom. If a course is discussion heavy, it is challenging to imagine ways to redesign without class discussions. Students want connection too: in surveys from spring, they asked for more connection to their peers and faculty. We all miss each other. In the many years I’ve taught online, I’ve never used Zoom or a synchronous model of teaching. I have found that asking students to write, read, make, share, celebrate can stand in for “talk” in class. They may not be asking for a synchronous approach, per se; they’re asking to be seen and heard. An asynchronous approach, with routine deadlines, gives them flexibility in their busy lives. Amplifying their work, asking them to notice each other’s work, helps all of us to feel seen and heard.

I use Zoom (or Google Hangouts or Skype) to collaborate with colleagues, so I understand the affordance. But, the way we’re using Zoom in classrooms does not look like the ways I use it to collaborate with my peers. When I use these platforms with students, I invite them to use the platform like I do with colleagues: webinars, virtual writing retreats, consultation sessions. In fact, the virtual writing retreats have been quite successful. We meet to check in, we work offline, then come back together for feedback. I can imagine building, making, playing with all kinds of ideas in this simple structure: check in, go do a thing, come back and get feedback on that thing. An opportunity we have in this moment is to connect students to colleagues in other places, students at other campuses who are researching similar ideas. We can invite an author to talk to our class about a reading on Zoom. I’m hopeful that we can all continue to imagine intentional ways to use video platforms.

What I dream about for the future of higher education in particular is that we support faculty and students as they figure out how to use the web and digital tools, like, for real. We need support in thinking about copyright, surveillance and privacy, accessibility, access, and equity. We should have spent the last 10 years inviting people to learn about the web, to really know how to navigate and make decisions about tools and platforms. Instead, we invited people to work in sandboxes behind schooled walls in the name of being safer or more accessible. Unfortunately, using a campus tool does not make it any more accessible: faculty who upload a reading as a jpeg instead of a pdf into the LMS did not make the reading accessible, for example. Faculty who upload all their student photos with email addresses without student permission are not making the space safer. Moving forward, we have an opportunity to use this moment to learn more about digital practices that live beyond any one tool. We have an opportunity to learn about the affordances and constraints of the web.

Kim Jaxon is a Professor of English (Composition & Literacy) at California State University, Chico and Co-Director of the Northern California Writing Project. Her research interests focus on theories of literacy, particularly digital literacies, the teaching of writing, course design, and teacher education. In her research and her teaching, she uses a variety of digital platforms to consider the affordances in terms of student learning and participation. She is currently a featured contributor for Connected Learning Alliance and the co-author of Composing Science: A Facilitator’s Guide to Writing in the Science Classroom. This spring, 2020, she was named Outstanding Teacher at Chico State and was previously awarded the California Association of Teachers of English (CATE) Teacher of Excellence-College Award. You can contact her on Twitter (@drjaxon) or on her website: https://kimjaxon.com/

Additional Resources:

- If you’re interested in the messiness of Kim’s course design process, here’s a draft for one of her fall 2020 courses: English 332. The completed version of the course here: https://kimjaxon.com/engl332/

- Links to all Kim’s courses can be found on her site (kimjaxon.com) in the sidebar.

- Connected Learning Alliance: resources for thinking about digital pedagogy.

- A previous piece about course design: “No Shortcuts in Course Design“

If you’re interested in resisting EdTech and need support, here are current resources you can point to when talking with administrators or fellow educators:

- Audrey Watters’ recent talks: “Building Anti-Surveillance Ed-Tech” and “Luddite Sensibilities and the Future of Education.” Her site has much more: Hack Education.

- Jesse Stommel and Sean Michael Morris’ “A Guide for Resisting EdTech: The Case Against TurnitIn.”

- Hybrid Pedagogy journal

- Shea Swauger’s “Software that monitors students during tests perpetuates inequality and violates their privacy” and “Our Bodies Encoded: Algorithmic Test Proctoring in Higher Education.”

Resources for accessibility in course design:

- Three Steps to a More Accessible Classroom, which ends with other useful links with an eye on accessibility.

- GrackleDocs, which checks Google Docs.

- Also, this resource both supports and critiques Zoom. Check out the Guide for Students on page 20.